this article deserves comment. i note it here in order to return to it later. here are a few thoughts from a talk that i gave this spring on the "achievement gap" aframth2010presentation04272010 and a welcome antidote to the, dare i say pessimism, of the study noted.

terrence's take

mathematics and the african american community: algebra in every home.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

Sunday, March 6, 2011

Algebra and the Black Church

what resources do we have in our community to encourage and support the endeavors of young african american boys and girls in the study of mathematics? how do we get our young men to spend more time with a pen and less time with the hair brush? smile.

from the new york times-

Black Churches Renew a Mission: Education

CHICAGO— Those who would save America's inner-city schools are discovering a long-neglected resource: the black church.

From after-school tutorials to summer schools, computer classes to family science activities, black churches are renewing their historic commitment to education. But now they are getting money from private foundations and some government agencies, who see black churches as their best link to children in neighborhoods beset by poverty, violence and school failure.

For years these donors shunned religious institutions, worried about the separation of church and state. But now many have come to believe that churches, by their very nature, can supplement what they see as gaping holes in public schools, providing moral or religious training and treating the whole range of social ills that doom many children to failure. To avoid church-state conflicts, most require that money go only to nonreligious educational programs. Filling a Gaping Hole

On a recent day here, more than 500 children sat in makeshift classrooms in churches around the city, racing to chalkboards to work out mathematics problems or drawing pictures of the solar system. In an unlikely pairing of science and religion, the National Science Foundation, a government agency, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a professional group, are financing hundreds of instructional programs in black churches here and around the country to improve math, science and computer skills.

The Association for the Advancement of Science has spent $800,000 in the last four years for such programs in 800 churches in 17 cities. Private foundations are also giving money. The Carnegie Corporation, for example, has given $2.3 million for church-based educational programs in nine cities.

Such church educational offerings include preschools, classes in how to be a parent and special programs tailored to young black men. Most of the children in the programs are not members of churches, but are often those the public schools have failed.

Black churches stepped up their educational programs as concern mounted over the deterioation of inner-city public schools.

"We are responsible who live here," said Rev. Willie Gable, whose Progressive Baptist Church in New Orleans is spending $100,000 this year on educational programs and computer training, with help from Association for the Advancement of Science and Apple Computers. "What's going on now in my community is something I can change. If each one of us reach one, teach one, we'll make a difference."

From their inception in the early 1800's, the predominantly Protestant black congregations in America have seen education as part of their mission, said the Rev. Alicia Byrd of the Congress of National Black Churches. Many founded schools and colleges to educate black children barred from white schools. But as the public system expanded, many churches retreated, Ms. Byrd said. In the last several years, churches have renewed their efforts.

"If you want to deal effectively with the black community you have to deal with churches," Ms. Byrd said. "One, because they have the constituency, two, because they have the commitment to community service, and three, because churches have begun to do things." Children Learning Amid the Homeless

One of the most ambitious projects in the country is here in Chicago, where more than 500 churches are working to improve the math, science and computer skills of the children they serve. This summer, 10 churches are offering summer school to the 500 students.

In Chicago, this Black Churches Project helps train church teachers and student tutors, designs the science, math and computer courses the churches offer, pays for field trips, recruits black science and math professionals to serve as mentors and speakers, and holds science and math workshops for families.

At the Excellent Way Church of God in Christ, a small storefront in one of Chicago's most violent and drug-ridden neighborhoods on the South Side, summer school is in session. Julia Ervin presides over two tables of students squeezed into the back of the room, across from the altar. Brightly colored maps of Africa and drawings of spaceships cover the walls. At the other end of the room, a woman in curlers sits watching television in an overstuffed chair, one of the homeless who use the church as a shelter.

Despite the distractions, the children are attentive, working in small groups with Mrs. Ervin and two teen-age tutors.

"You've gone to the store," Mr. Ervin said to a young girl named Rose. "You have $1.02 and you purchased a pair of socks for 27 cents. Stop chewing your gum. Add or subtract? What are you going to do? Subtract? Good."

On average, said Dondieneita Fleary, who directs the Black Churches Project, which is administered by the Urban League here,these children are three grade levels behind in school. One child has just been taken away from his mother because she smoked crack when pregnant with his younger sister.

But the children in the class were brimming with confidence, and eager to show off for a visitor. "I can't wait to get to school to get A's," said Michael Dameron, 10 years old, his words tumbling out. "Here I got lots of A's, and I like this because it's a church and so if somebody lies here they get struck down. I like science. We do the solar system, and I found out the Sun is a star. And Mrs. Ervin said Pluto is the smallest planet, but me and him found out Mercury was smaller."

Michael's tutor, Antwan Clark, who will attend the Illinois Institute of Technology next year, is himself a graduate of a special program to encourage talented minority math students, also financed by the Black Churches Project. Professionals Guide Science and Math

The project grew out of a nationwide effort by the Association for the Advancement of Science to improve minority students' math and science skills by joining forces with existing nonreligious church education programs. A survey the group conducted in 1987 found that most black churches ran after-school homework tutorials, but few taught math or science well. So the science association compiled a manual suggesting simple science activities teachers and parents could do with children, began conducting training workshops for churches, and paid for such activities as field trips to museums and science career days. "In trying to expand the pool of minorities who go into science careers, we wanted to reach a different tier," said Yolanda S. George, the association's deputy director for education and human resources. "It seemed like the churches were a good way of getting to a population that nobody may be reaching."

In Chicago, the black churches' response was so enthusiastic that the Urban League expanded the project's scope. The group hired Ms. Fleary as full-time director and won financing from the National Science Foundation, as part of a $15 million effort in 12 cities to teach minority students more math, science and computer skills.

In addition to scientific groups, private foundations are also financing a wide range of projects in black churches around the country. The Carnegie Corporation, for example, supports Project Spirit, a nine-city network of after-school programs in churches that teach moral values and black history along with math, science or reading. The Community Foundation of Southeastern Michigan has given small grants to more than 40 black churches in the Detroit area. The Lilly Endowment helps finance the Congress of National Black Churches, which administers Project Spirit.

Many of the programs, which must demonstrate progress to get more financing, have documented remarkable success in improving both grades and behavior.

"There clearly has to be some way to link public education with churches as a resource," said Jacqui Burton, program director for religion at the Lilly Endowment. "I think we probably have to re-educate our community and school systems to see this as an advantage, in spite of this church-state problem that people always bring up." Emphasis on Ethics Part of Curriculum

Many backers of the programs see as churches' great strength the public schools' great taboo -- an emphasis on ethics and spirituality that runs through most of the programs. Wilhelmina Varner-Quick, a public school principal in Detroit, for example, founded an after-school tutorial program at her church because she was increasingly disturbed by the amorality of young children in her school.

"They did not know what they did was wrong," she said. So, as a lure to parents, she offered math and reading tutoring at her church, the Southwestern Church of God. At the end of the afternoon, the children gather in a "magic circle," where the teacher "teaches them values, not with Scripture, but sound values about honesty, patience, tolerance, drugs, teenage pregnancy, everything," Ms. Varner-Quick said.

Even though the program is not religious, Ms. Varner-Quick said she felt it belonged in a church, rather than a public school. "If a parent chooses to send them here, it relieves you of the responsibility about being careful of what you say," she said. "With the public school, you have boundaries you have to remain closed in."

It is hard to escape religion in a church, even if educational programs are not explicitly religious. In the Avalon Park United Church of Christ in Chicago, two little girls recently raced each other across a blackboard, trying to be the first to finish math equations. Above their heads were a series of posters, with Biblical adages. Scriptures Coexist With Science

Some church educational programs do include direct religious teachings or references. In Chicago's South Shore Baptist Church, the summer school ends its day with "Christian growth." A young group of students heard about Good Samaritans and exchanged stories about when people had helped them. An older group of students discussed ethical problems, such as what to do if you see someone stealing something but you yourself have done wrong in the past; Biblical passages are used in the discussion.

Ms. Fleary said many programs opened and closed with short prayers. Some pose problems like reconstructing Noah's Ark, or measuring things in cubits. Ms. George of Association for the Advancement of Science said that some ministers in Chicago and Pittsburgh were initially wary about teaching evolution, so the foundation has focused on physical sciences. Many church teachers sidestep the debate about evolution, Ms. Fleary said, by outlining what scientists believe, what the Bible says, and letting the children puzzle out the contradictions.

Some parents, particularly Muslims, Ms. Fleary said, have occasionally protested the Christian religious content. 'They said they didn't want their kids getting religion, they just wanted math and science," she said. "I said, it's part of the ministry of the church, why churches want to do it. I tell them, try other programs, or tell them something different at home."

Church-state distinctions are often a matter of interpretation and restrictions vary by government agency. Roosevelt Calbert, head of minority programs at the National Science Foundation, said he was not aware of any specific restrictions on the use of his agency's money by black churches, partly because the foundation had just begun to give them money.

Officials at the Department of Education said they did not know of such grants now, but that in the past they had monitored such programs carefully to make sure there was no religious content. Attacking a Range Of Social Problems

What many of the church programs also have in common is something that has often eluded public schools -- an ability to attack the whole range of social problems that are often the root of educational failure. Many active black churches also house homeless shelters, form partnerships to build housing, offer supervised after-school activities for children whose parents are working, and reach out to parents.

In Chicago, Ms. Fleary recruits children directly from the public schools, building relationships between pastors and principals, teachers and parents. Parents and guardians who allow their children to participate in the after-school or summer church programs are invited to special church services, where Ms. Fleary also holds a special workshop. Scrounging through church kitchens, she assembles materials for easy science experiments and demonstrates them for parents, showing them how they can reinforce the classes at home.

And in New Orleans, Mr. Gable uses his computer center to offer training in employable skills to both children and their parents. He offers a special program for teen-age parents, which is partly financed by Louisiana's Department of Education.

"Because it's such a poor area, we become everything, counselor and babysitter until Mama comes home," he said. "We've been able to be that other shoulder and other ear for parents and kids, for someone to talk to about the problems they're having."

Photos: Lakisha Scott working on math problems at an afternoon instructional program at the Avalon Park United Church of Christ in Chicago. (Steve Kagan for The New York Times) (pg. A1); With financial help from foundations and some government agencies, black churches are renewing a commitment to education. Antwan Clark, a student, tutoring, from left, Charles Evans, Jason Martins and Michael Dameron at the Excellent Way Church of God in Christ in Chicago. (Steve Kagan for The New York Times) (pg. A

does this reflect what is happening in your community?

what was the date of this article? By SUSAN CHIRA,

Published: August 7, 1991

smile and be well.

p.s please follow the blog.

Thursday, January 27, 2011

the challenge at hand

In 2009, 49,562 doctorates were awarded by American universities. As previously reported by JBHE, there were 2,221 black U.S. citizens or permanent residents in this country who earned a doctorate in 2009. This is an all-time high.

But not all the news is good. African Americans earned only 1.6 percent of all doctorates awarded in the physical sciences by American universities. The 25 blacks who earned a Ph.D. in mathematics were only 1.6 percent of all doctorates in the field given out by U.S. universities. African Americans earned only 1.8 percent of all doctorates in engineering.

In 2009, 1,418 doctorates were awarded in the fields of astronomy, astrophysics, theoretical chemistry, paleontology, number theory, logic, marine science, chemical and physical oceanography, nuclear physics, nuclear engineering, agronomy, horticulture, wildlife/range management, animal breeding and nutrition, Spanish, and the classics. Not one of these 1,418 doctorates was awarded to an African American.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

a decade by the numbers

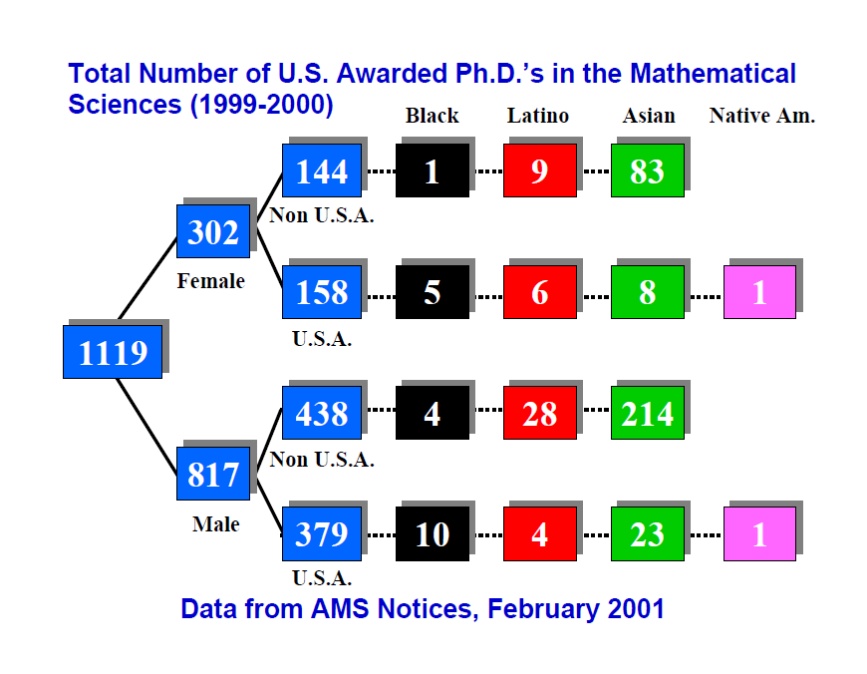

a quick note: i came across these wonderful graphics which

(i) explains things perfectly and

(ii) illustrates clearly the work that needs to be done. enjoy.

Monday, March 1, 2010

the joy of x-steven strogatz

from the nytimes: Steven Strogatz is a professor of applied mathematics at Cornell University. In 2007 he received the Communications Award, a lifetime achievement award for the communication of mathematics to the general public. He previously taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he received the E.M. Baker Award, an institute-wide teaching prize selected solely by students. “Chaos,” his series of 24 lectures on chaos theory, was filmed and produced in 2008 by The Teaching Company. He is the author, most recently, of “The Calculus of Friendship,” the story of his 30-year correspondence with his high school calculus teacher. In this series, which appears every Monday, he takes readers from the basics of math to the baffling. check out his latest post "the joy of x": he writes-"Algebra, for example, may have once struck you as a dizzying mix of symbols, definitions and procedures, but in the end they all boil down to just two activities — solving for x and working with formulas.

Solving for x is detective work. You’re searching for an unknown number, x. You’ve been handed a few clues about it, either in the form of an equation like 2x + 3 = 7, or, less conveniently, in a convoluted verbal description of it (as in those scary “word problems”). In either case, the goal is to identify x from the information given". it is well worth reading. be well.

Monday, February 15, 2010

twokayten

i trust that all is well. a happy new year to you. it has been six months since i last wrote a sentence in this blog! as you have perhaps surmised, brooklyn is a "black hole" which sucks up everything in sight. smile. to put it mildly, i have been a bit overwhelmed by the responsibilities of family, teaching, research, guidance, and all things brooklyn since my return to nyc in june 2009. prior to my last note i was preparing to attend the 2009 caarms conference at rice university in houston.

on my return to south hadley, ma from houston texas i loaded up my belongings, said my goodbyes

and headed home to the peoples republic of brooklyn.

on my return to mec in july, i was tasked with teaching a course for intermediate algebra students and another one on math for elementary school teachers. the intermediate algebra reminded me of the very real challenges our community faces as we try to widen the circle of literacy. one strategy for dealing with this came to me during my math for elementary school teachers. it was a challenging and wonderful experience and it led me to initiate the development of a medgar evers college math circle. this effort i hope will begin to bear some fruit in few years. thus far we have been able to pilot a small bit of our material at the immaculate heart of mary middle school in brooklyn. the 6th, 7th and 8th graders were very receptive to some of the material presented and my intuition suggests that this type of effort can play a positive role in changing attitudes towards the learning of mathematics among middle and high school students in brooklyn. the goal now is to find some funding for this endeavor. check out the intro lecture. mathcircleinitiative02012010 . another project in which i have been involved is the "free text book movement", the idea is to use technology to ultimately eliminate the cost of the text for college students, in particular the poor one. Here is the goal-this is primarily the work of john velling at brooklyn college and i have been involved small role in aiding the roll out and refinement of this effort. check out an early version of the online calculus text. i used this last semester in my in my precalculus class and i am using it again in both my precalculus and calculus classes. this is the future. folks should also check out this excellent online resource for children. for those of you hooked on the iphone check out this article: algebra comes to the iphone. recently i visited san francisco as part of my efforts on this front. i am part of a small project which is designed to create experiences such as this for our undergraduates.

at some point i would like this to be a standard part of the experience of our majors at mec. it is important not to be diverted from the task. a recent article questions the efficacy of the “algebra for all” programs. this is a generational project. it's slow tough going. smile and be well.

i'll try to write a bit more frequently this year.